THE ART OF REVISING POETRY

THE ART OF REVISING POETRY: 21 U.S. POETS ON THEIR DRAFTS, CRAFT, AND PROCESS, edited by Charles Finn and Kim Stafford. Bloomsbury Academic, 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK, 2023, 156 pages, $20.96, paper, www.bloomsbury.com.

https://www.kimstaffordpoet.com

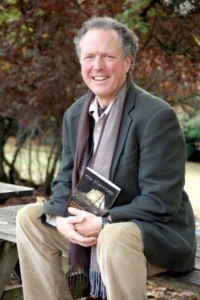

For this week, a departure from the usual one-poet book. I came across The Art of Revising Poetry last year while in Livingston, Montana, where I bought On a Benediction of Wind: Poems and Photographs from the American West—poems by Charles Finn, photography by Barbara Michelman.

When I looked up Finn to learn more about him, I discovered that he and Kim Stafford—a poet well known to me—had collaborated on an anthology of poems and essays about revision, not yet released. I put it on my wish list, and in December I found it at my library. (I’m going to have to buy my own copy.)

The opening essay is worth the price of admission, and includes a list of 12 suggestions for revision. The first:

- How could the poem’s title be more intriguing, prophetic, indelible? It’s been said the title of the poem holds about 20 percent of the poem’s overall effect. How can a poet tinker until the title alone compels? (p. 3)

The 21 poets include Finn and Stafford, also Abayomi Animashaun, Naomi Shihab Nye, Jane Hirshfield, Joe Wilkins, Shin Yu Pai, CMarie Fuhrman, Prageeta Sharma, Frank X Walker, Beth Piatote, Sean Prentiss, Shann Ray, Philip Metres, Rose McLarney, Yona Harvey, Paulann Petersen, Todd Davis, Tami Haaland, Jimmy Santiago Baca, and Terry Tempest Williams.

(I had planned to offer a sampling of names, then I just kept going.) The list includes poets known to me and unknown. The approaches to revision are as diverse as the poets. They echo one another, of course—they’re writing about the same topic, after all—but each poet adds something unexpected. Not one disappoints.

As I read, I kept writing out passages in my notebook. “My revision process is, overall, one of inquiry,” Rose McLarney writes in “Identifying Gems” (p. 57). In “Finding the Language, Finding Story” (a gorgeous essay that is also about raising a child), Joe Wilkins shares a strategy I honestly had never thought of: “I usually write in couplets (you can’t hide anything in couplets, all that white space forces you to interrogate every word)” (p. 18).

In “Emptying the Zendo,” Shin Yu Pai admits that she doesn’t revise very much, then elaborates:

Revision, for me, is like polishing a gem to bring out its beauty. However, this working and reworking of the stone also changes its rawest qualities and alters its energy. The place where I decide to put down the pen and stop fussing with the poem is not the place another poet, teacher, or scholar might choose to end. Ultimately, we find our own relationship to our voice and our objects through reading, practice, and deep listening. In this way, we are our own teachers. —Shin Yu Pai

This might be good advice for life, as well as for writing. We find our own relationship through using our own voice, but also reading, practice, and deep listening.

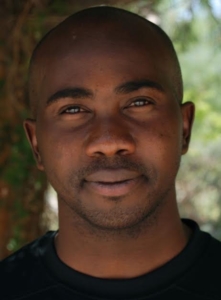

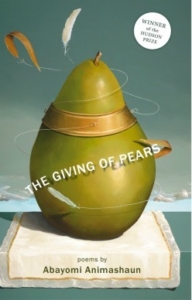

For each poet, we encounter first a photo of an early draft, usually hand-written, then a typed “first” draft, next the final version, and finally a short essay about the revision. Here is Animashaun’s final draft:

Exodus

When the last immigrants

Walked out the gatesFireworks lit up the sky

Horns and sirens blaredFrom every window

Flags drapedThe country at last

Was itself again.At the park, townsfolk

Celebrated new liberation day—They cheered as foreign clothes

Were burned in pilesDanced when ethnic foods

Were flushed down sewersAnd monuments to migrants

Were lassoed and pulled downIncluding statues

Of the town’s founders—Immigrants some say

From the horn of Africa—Whose clay heads now dangle

From a rope in the heart of town.—Abayomi Animashaun

In his essay, “Discipline and Unknowing,” Animashaun writes about the journey he took with this particular poem, and about what happens with every poem:

I never know where the writing will lead, but I accept the gift of each word, of each phrase, with the faith that each will yield in its own time as long as I continue to listen and remain steadfast . —Abayomi Animashaun

(To learn more about Animashaun and his books, visit his website:

http://www.abayomianimashaun.com/books.html.)

http://www.abayomianimashaun.com/books.html.)

I find myself wishing I were teaching a class where I could assign this book and discuss it. I’ll shut up now and let you find your own copy. The publisher is currently offering it at a discount: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/art-of-revising-poetry-9781350289277/.

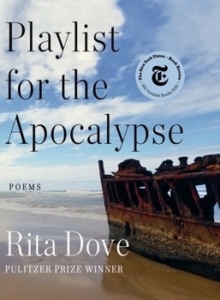

personal. “After Egypt” takes up the long history of emigration, displacement, and ghettoization. The section, “A Standing Witness,” emerged when she was tasked to collaborate on “a song cycle, bearing witness to the last fifty-odd years.” It begins with an epigraph:

personal. “After Egypt” takes up the long history of emigration, displacement, and ghettoization. The section, “A Standing Witness,” emerged when she was tasked to collaborate on “a song cycle, bearing witness to the last fifty-odd years.” It begins with an epigraph:

not already subscribed to her near-daily blog

not already subscribed to her near-daily blog