Esther Altshul Helfgott: Listening to Mozart

LISTENING TO MOZART: POEMS OF ALZHEIMER’S, Esther Altshul Helfgott. Cave Moon Press, 2014

A more personal blogpost today. Instead of hinting about and writing around what’s going on, I want to simply admit that it has been one catastrophe after another here all year, more and more noticeable since our dog (my emotional support animal, it turns out) died in October.

My husband is not well, and despite all evidence to the contrary, he still wants to be in charge of the world, his and mine. As a result of his attempt to hold onto his independence, we’ve had EMT’s in our backyard, multiple Urgent Care visits, some good days (celebrate those!) and many days crammed overfull with anxiety (for me). The wheels of health care are turning very very slowly, and we don’t have a diagnosis for what’s going on. But now that 1) he’s not driving (and seems to have let that go), and 2) I have gotten our taxes done, I’ve calmed down quite a lot. That helps.

My husband is not well, and despite all evidence to the contrary, he still wants to be in charge of the world, his and mine. As a result of his attempt to hold onto his independence, we’ve had EMT’s in our backyard, multiple Urgent Care visits, some good days (celebrate those!) and many days crammed overfull with anxiety (for me). The wheels of health care are turning very very slowly, and we don’t have a diagnosis for what’s going on. But now that 1) he’s not driving (and seems to have let that go), and 2) I have gotten our taxes done, I’ve calmed down quite a lot. That helps.

Before the steepest part of the dramatic arc took off, I attended a reading in Seattle and ran into an old friend, Seattle poet Esther Altshul Helfgott. Among many other accomplishments, Esther founded the “It’s About Time Writer’s Reading Series,” which meets monthly in Ballard and is now in its 35th year. I’ve known her for decades. As she has two books navigating Alzheimer’s disease with her husband, Abe, I told her what was going on at my house. She reached into her bag and took out a copy of this book. She also told me I needed a therapist and a support group.

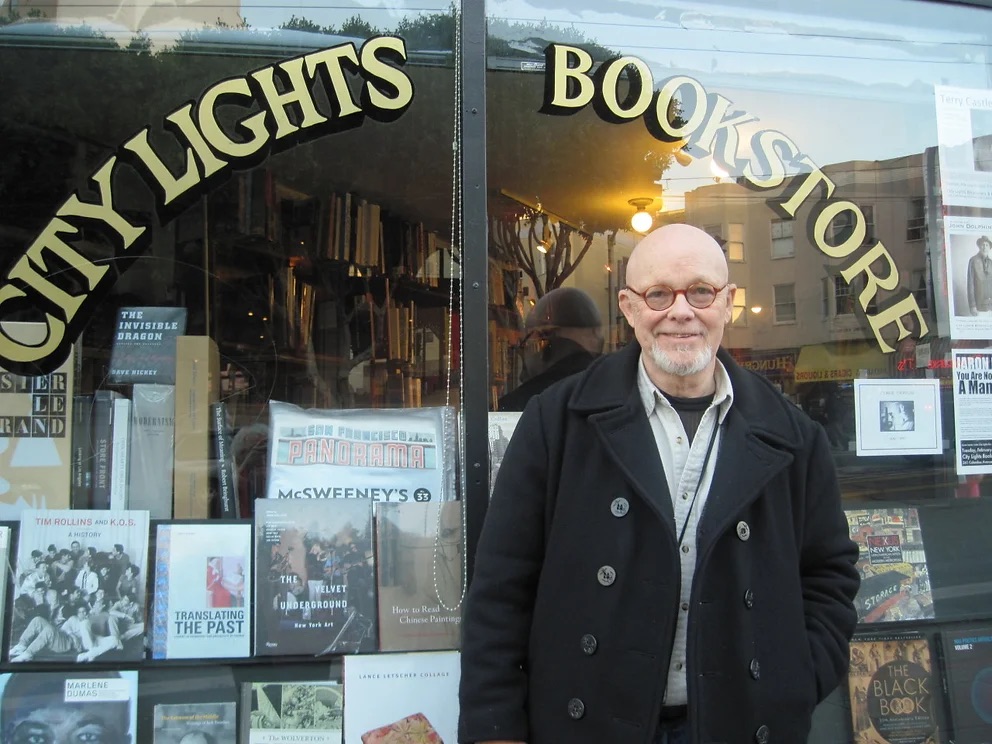

Esther Altshul Helfgott, image from the Two Sylvias website

Listening to Mozart is, in the words of Michael Dylan Welch, “a bouquet of short poems [that radiate] the sharp and sad fragrance of loss.” They were written after Abe’s death, and reading them helped me imagine moving through the stages of grief I’ve been stuck in—anger and denial—and begin to break through to something else.

I don’t agree

with Bishop in One Art—

that loss

is no disaster

she means the opposite—

loss is all disaster

These tanka-like meditations are as much about acceptance as they are about loss, and they helped me to remember that someday this will be over, and I’ll have three daughters who have lost their father. They reminded me that some day I, too, will have to deal with his loss.

when I

awoke this morning

I thought your

funeral was today—

it was three years ago

The poems are about loss, but they are riddled with hope. As time moves on and the poems continue, Helfgott begins to put her life with Abe, and after Abe, into perspective. Cleaning house, going to the bookstore, walking her dog.

a leaf falls

I watch

you pick it up

you disappear

What I’ve been working through is the realization that the man I married has been gone for a while, for long enough that I’ve found it difficult to remember that guy I held hands with, walked on beaches with, adopted three daughters with, stood on sidelines of countless soccer games with…the man who taught college English for 40 years, the man who retiled our kitchen, built a writing cabin for me in our back yard, built tables and beds…took care of every possible home repair. Up until a day or so ago, it seemed impossible to see that man as also this one. Withdrawn from me, secretive, never finishing a project, forgetting ingredients in favorite recipes, getting into one car accident after another…

And there’s also—my own bad attitude. I’ve been so …ticked off, not wanting to do this, that it blinded me.  After all, I went through it with my mother (for almost 10 years!). It’s not fair!

After all, I went through it with my mother (for almost 10 years!). It’s not fair!

But our daughters are still young. Or young-ish. They’re not going to step in and take over for me while I book a flight for elsewhere. If someone is going to pull this experience together and unite our family around it, that someone will have to be me. I think of all the compassion and caring I poured into our old dog. That’s what I’m going to have to summon now, for my husband.

Esther’s poems helped me begin the journey back to my right mind. These poems and many phone conversations with patient friends, and (finally) a therapist.

I have been waiting for my husband to say, “Oh, I see what’s going on, let’s talk about it.” Waiting for him to agree to be looked after, waiting for him to give me permission to pay the bills (which have been going unpaid). Waiting for him to help me—as he always did, back in the day—get through this hard thing. Meanwhile, I’ve had multiple people (including Esther, months ago) tell me that the partnership is over, “your husband is gone,” and now it’s my responsibility to make good choices for both of us. Obviously, I still have a lot to wrap my mind around.

And there’s that persistent part of me that wants to say—you go on ahead, I’ll write a poem about it!

The last poem in Listening to Mozart gives me hope that a much better frame of mind will come. All I have to do is stay on the path.

I didn’t know

I was writing love poems

to you Abe—

I was just writing

and love came out

Esther is also the author of Dear Alzheimer’s: A Caregiver’s Diary & Poems (Cave Moon Press, 2013). You can learn  more about her and her journey with Abe at the Jack Straw Cultural site, where she was a fellow in 2010 (be sure to listen to the interview), and, more recently, you can find her at this page at Two Sylvias.

more about her and her journey with Abe at the Jack Straw Cultural site, where she was a fellow in 2010 (be sure to listen to the interview), and, more recently, you can find her at this page at Two Sylvias.

Fargnoli’s Necessary Light (Utah State Univ. Press, 1999). These, perhaps more than anything, help.

Fargnoli’s Necessary Light (Utah State Univ. Press, 1999). These, perhaps more than anything, help.

somewhere, someone had given me his book of poems. On Saturday at the launch of I Sing the Salmon Home, he said hello and introduced himself. Today, I rummaged through my bookshelves, found his book, and read it all the way through, even the end notes (which are sort of a poem, themselves).

somewhere, someone had given me his book of poems. On Saturday at the launch of I Sing the Salmon Home, he said hello and introduced himself. Today, I rummaged through my bookshelves, found his book, and read it all the way through, even the end notes (which are sort of a poem, themselves).