Pablo Neruda (1904-1973)

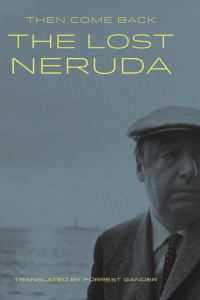

THEN COME BACK: THE LOST NERUDA POEMS, Pablo Neruda, trans. Forrest Gander. Copper Canyon Press, PO Box  271, Port Townsend, WA 98368, 2016, 163 pages, $23 ($17 paper), www.coppercanyonpress.org.

271, Port Townsend, WA 98368, 2016, 163 pages, $23 ($17 paper), www.coppercanyonpress.org.

Well. What does one say about Pablo Neruda? Lauded as the greatest poet of the Americas, the greatest poet of the 20th century, influencer of all subsequent generations of … Nobelist … etc. I can’t imagine what I might add.

All I will say is that I attended the Seattle Arts and Lectures presentation of this book — back in those lovely old pre-Pandemic days, and heard a number of the poems, first in Spanish (which was like listening to music), then read by Forrest Gander (a remarkable poet in his own right), the translator. The book is part poetry collection, part artifact, with color plates. It’s funny, and loving, and generally just worth the trip.

I’m compelled to share a scrap from poem #20. Although Neruda died well before our current age of iPhones, it so anticipates our enslavement: “raising my arms as though before / a pointed gun, I gave in / to the degradations of the telephone.” “I came to be a telefiend, a telephony, / a sacred elephant, / I prostrated myself whenever the ringing / of that horrid despot demanded” — and so on (pp. 60-61).

The Prologue, by Gander, is worth reading (and rereading). He tells about how these poems overcame his reluctance to do the translation (“The last thing we need is another Neruda translation.”) And he shares the process with us — not only his encounter with the locked vault of the Neruda archives, but with his own journey through the poems, often hand-written on menus and placemats.

Once I moved through the introductory material and into the poems, it was all over….When the glowing screen revealed the lost poems, hours suddenly clipped by in minutes. I neglected to come in for dinner. The windows opaqued with night. The world hushed as I translated the first three poems. The truth is that I disappeared from myself. I was concentrated entirely into the durable moment of translation — which begins in humility, a sublimation of the self so extreme that the music of someone else’s mind might be heard. And for a while, no remnant of me existed outside of that moment.

— Forrest Gander, “The Prologue”

“For a while, no remnant of me existed outside of that moment.” I can think of no better reason to come to poetry.

17.

I bid the sky good day.

There is no land. It slipped away

from the boat yesterday and last night.

Chile’s been left behind, just

a few wild birds

follow us drifting and raising up

the dark cold name of my homeland.

Accustomed as I am to goodbyes

I didn’t strain my eyes: where

are my tears bottled up?

Blood rises from my feet

and roves the galleries

of my body painting its flame.

But how do you stanch the moaning?

When it comes, heartache tags along.

But I was talking about something else.

I stood up and beyond the boat

saw nothing but sky and more sky,

blue ensured in

a web of tranquil clouds

innocent as oblivion.

The boat is a cloud on the sea

and I’ve lost track of my destination,

I’ve forgotten prow and moon,

I don’t remember where the waves go

or where the boat carries me.

There’s no room in the day for earth or sea.— Pablo Neruda

Click on the links above to read more about Neruda and Gander. Also, you can find a description of the project and links to the paperback edition at Copper Canyon: https://www.coppercanyonpress.org/books/then-come-back-the-lost-neruda-by-pablo-neruda-forrest-gander/.

Forrest Gander

“Orchard” in a small Modern Library anthology with a blue cover: Twentieth Century American Poetry. Published by Random House in 1944, and again in 1963, that “Twentieth-Century” seems poorly chosen, or at least arbitrary. I mean, why did the editors decide to include Emily Dickinson? Perhaps because she was published in the 20th century? But in 1944, we still had half a century to survive and write about!

“Orchard” in a small Modern Library anthology with a blue cover: Twentieth Century American Poetry. Published by Random House in 1944, and again in 1963, that “Twentieth-Century” seems poorly chosen, or at least arbitrary. I mean, why did the editors decide to include Emily Dickinson? Perhaps because she was published in the 20th century? But in 1944, we still had half a century to survive and write about!