Parker Palmer’s A HIDDEN WHOLENESS

I have been walking through my Writing The Circle series with a small group of followers, and sharing a bit about a personal crisis that I’m dealing with at present–my husband is ill, diagnosed thus far with depression and anxiety–which has taken me and my family completely by surprise. It’s taken over a lot of the space I thought was going to be devoted in 2019 to my writing, and I have my moments of bitter resentment. I also have moments of great patience, kindness, and fortitude–and I hope that it is these moments that will prevail.

One of my readers from the small group challenged me to share on the blog at least some of what I’ve been dealing with. Her thinking (I think) was that the newsletters get lost in email-land pretty quickly, but the blogposts create a more permanent and retrievable record.

And…I sit with my fingers on the keyboard for a long while, considering whether or not I should…

Somehow–I’m just not ready. Not today.

I imagine the health crisis at my house has affected me at least a little like the great snowstorm of 2019 has affected all of us–this snowstorm that Cliff Mass says we’ll be telling our grandchildren about. We believe that we have control of our lives, and then life itself catches us by surprise, knocks us down, and dares us to get up again.

But I remember how I began this series, in Prompt #1–life does happen, terrible things happen. The only actual control we ever have is of our own response.

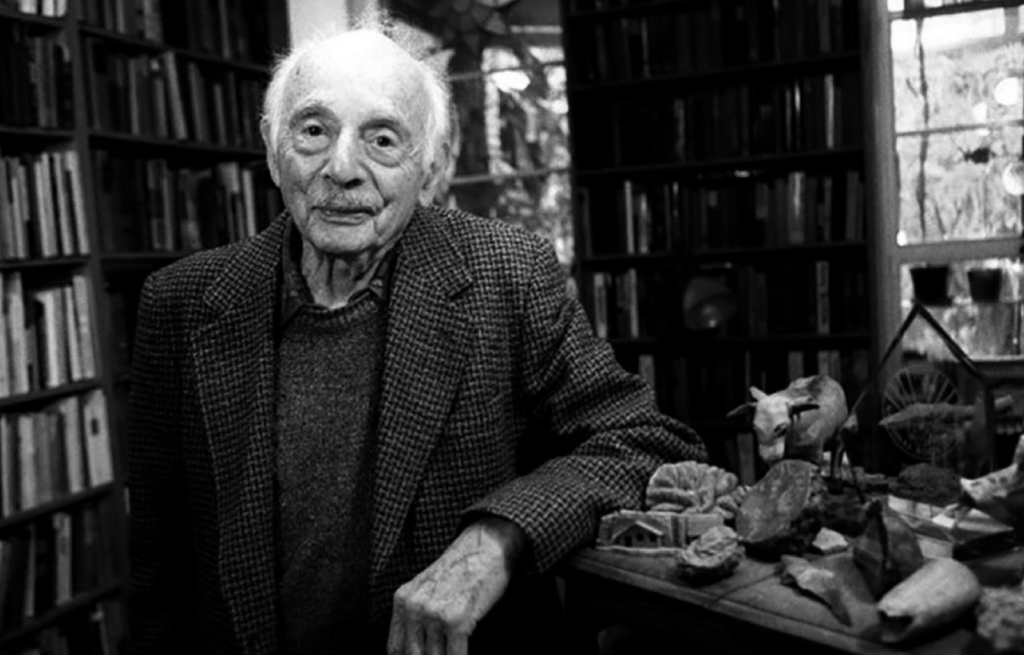

One response I’ve made, thus far, is to dig out my copy of Parker Palmer’s A Hidden Wholeness: The Journey Toward an Undivided Life. As much as anything else, this is a book about Palmer’s debilitating depression and how he came back from it. I found it on a shelf with books about teaching; I had forgotten it was about depression–well, entirely apt!

Here’s just one of the passages that, in previous readings, I’ve underlined and highlighted and annotated:

I pay a steep price when I live a divided life–feeling fraudulent, anxious about being found out, and depressed by the fact that I am denying my own selfhood. The people around me pay a price as well, for now they walk on ground made unstable by my dividedness. How can I affirm another’s identity when I deny my own? How can I trust another’s integrity when I defy my own? A fault line runs down the middle of my life, and whenever it cracks open–divorcing my words and actions from the truth I hold within–things around me get shaky and start to fall apart. (5)

And here’s a passage I copied into my journal this morning:

“This is the first, wildest, and wisest thing I know,” says Mary Oliver, “that the soul exists, and that it is built entirely out of attentiveness.” But we live in a culture that discourages us from paying attention to the soul or the true self–and when we fail to pay attention, we end up living soulless lives.” (34-35)

I once heard the poet Chana Bloch say, in regards to her brush with cancer, “I am going to survive this, and I am going to write about it.”

That’s what I’m going to do, too.

Maybe you’ve heard this before, as I seem to see it everywhere lately:

Maybe you’ve heard this before, as I seem to see it everywhere lately:

When I was in an MFA program for poetry, one of my professors chided me for my reliance on narrative, on story. “Stop making sense,” he advised.

When I was in an MFA program for poetry, one of my professors chided me for my reliance on narrative, on story. “Stop making sense,” he advised.