Random thoughts about daughters

Alternate title: the writer with children. This started out as one sort of reflection, and turned into another.

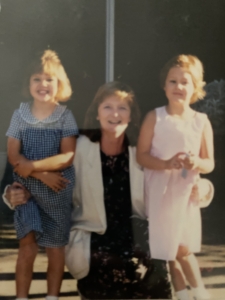

My older two daughters turn 31 today, which I find completely unbelievable. Their baby sister turns 25 in 10 days.

My older two daughters turn 31 today, which I find completely unbelievable. Their baby sister turns 25 in 10 days.

I was never a young mom. I was 37 when we adopted Annie and Pearl, and 43 when Emma came along.

Thinking about it, I’ve always been a late bloomer. Which is why, at age 37, I was in graduate school, post-classes, pre-exams. I was also teaching one class each quarter, which paid my tuition and a stipend.

Maybe my friends should have warned me that I’d lost my mind. Instead everyone was astonished and supportive. I’m immensely grateful.

But I did kind of lose my mind, or at least my way. I spent the first six months avoiding my graduate work and being a crap teacher, too. I got away with it for a while, until I didn’t. One memorable (ugh) quarter, I was so wrung out and sleep-deprived that I had the absolute worst student evaluations of my life. It was humiliating. I wanted to hide under a rock until it all went away.

Instead, because of that class, I completely overhauled my strategy. Or strategies. Because of the brutal honesty of those students, I learned to be all in when I was prepping for teaching, when reading their papers, and — especially — while in the classroom or in conference with them.

Much of the time, I was all in with my daughters, too. Some of my best memories are of lying on the floor with them while they played, taking them for walks, blowing bubbles on the front porch, reading books. Going to see their grandparents. In time, I figured out how to do a version of parallel play, and while they were busy doing their thing, I veered off into my own books.

Because of my daughters, I completely restructured my Ph.D. I chose advisors who were parents (two of them  women who had children while in graduate school). I was in 19th century American literature studies; the centerpiece of my dissertation was Nathaniel Hawthorne, but other chapters included two women authors who remained childless, a woman author who abandoned her children, and a woman author whose only child died young. Realizing this, I added an introductory chapter on Anne Bradstreet — if AB could get up early in the morning, given her eight children, “stealing the hours from household duties,” and write, then surely I, with my paltry two, could get up early and write. For years a version of “shehad8” was my computer password.

women who had children while in graduate school). I was in 19th century American literature studies; the centerpiece of my dissertation was Nathaniel Hawthorne, but other chapters included two women authors who remained childless, a woman author who abandoned her children, and a woman author whose only child died young. Realizing this, I added an introductory chapter on Anne Bradstreet — if AB could get up early in the morning, given her eight children, “stealing the hours from household duties,” and write, then surely I, with my paltry two, could get up early and write. For years a version of “shehad8” was my computer password.

When did I write? I have a vivid memory of sitting in an outdoor cafe with two babies asleep in the stroller beside me while I worked on my Bradstreet chapter. I discovered that if I took them for a drive they would fall asleep and I could pull the car over and write. Early mornings were best. 4:30-6:00 — after which it was time to shower, dress, and race to the park-n-ride. (Riding the bus to the U district gave me an extra half hour of prep time.) Around then, I was awarded a 2/3 adjunct position, contingent on finishing my dissertation. This persuaded my husband (always freaked out about money) that we could put the girls in part-time daycare.

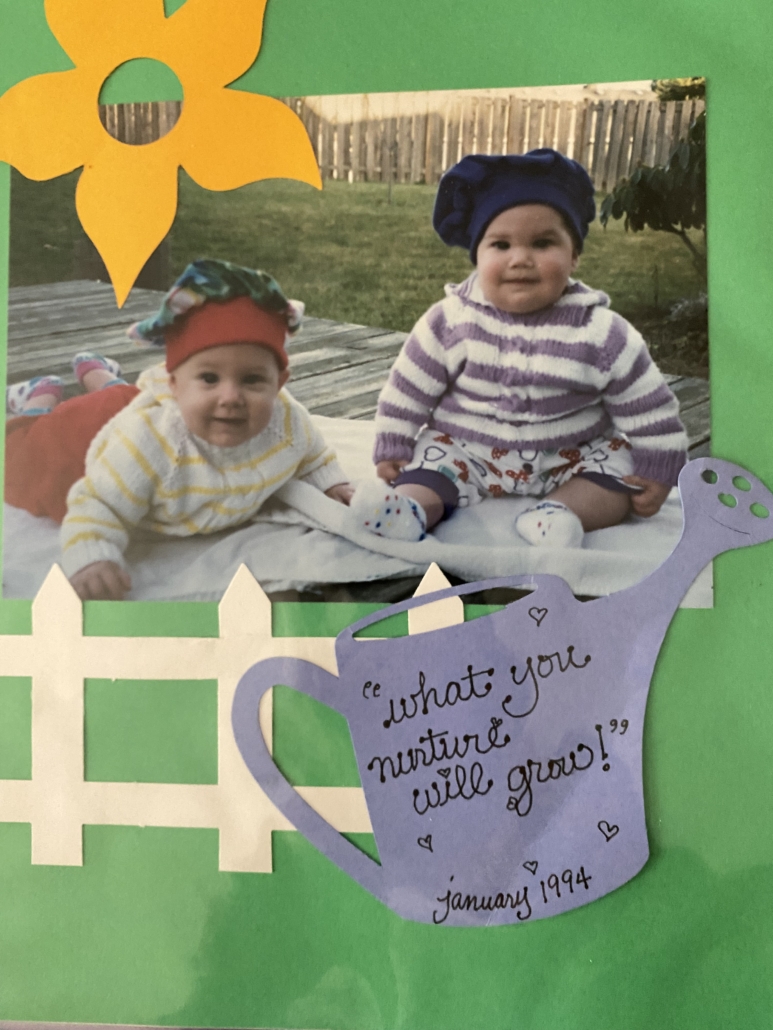

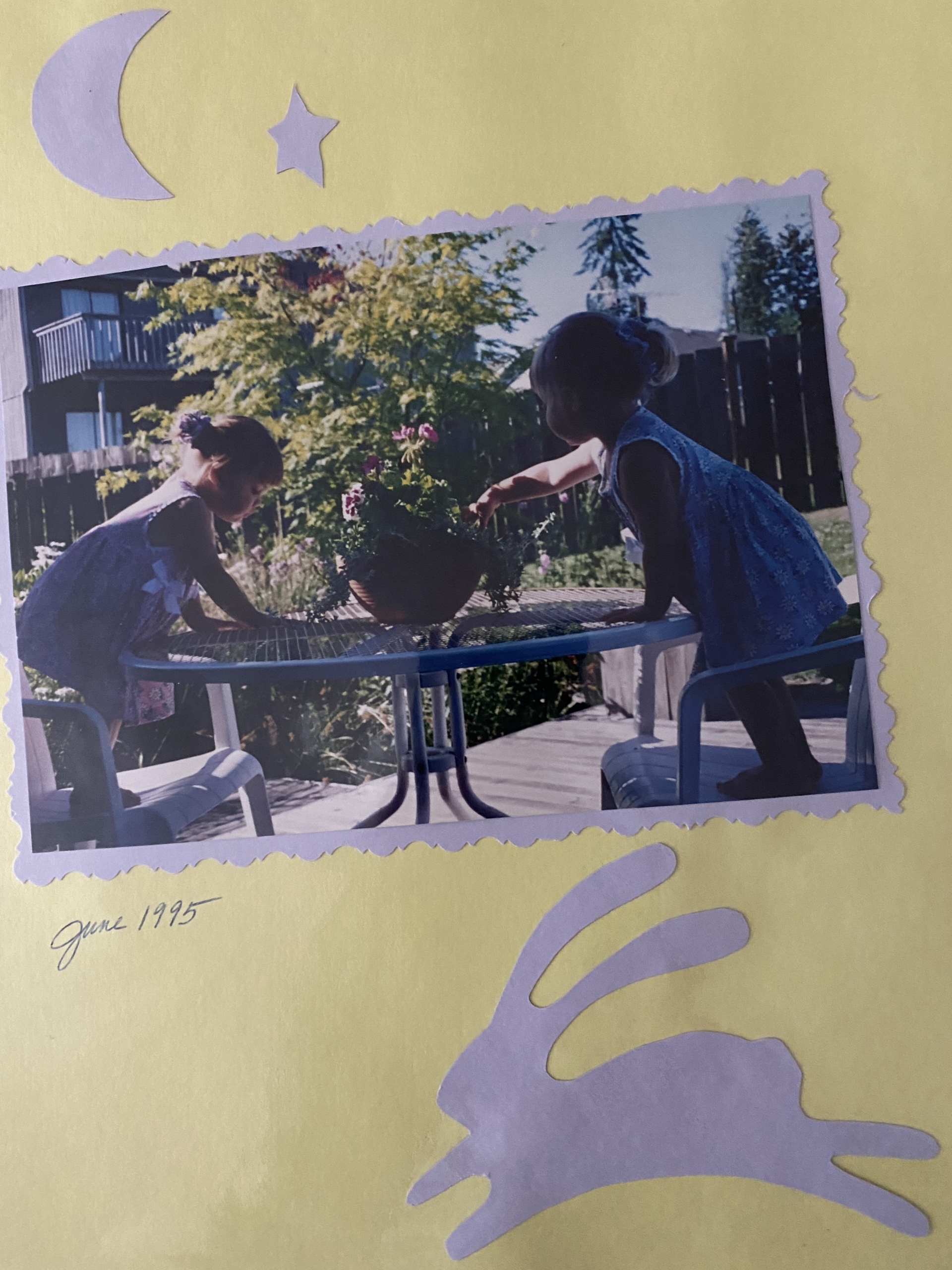

It wasn’t as efficient as I’m making it sound. I was a complete nut for taking photographs and scrapbooking (for a relatively short time, I promise you) — and writing about my daughters. I documented their every step. I signed the girls up for a twin study about language; I wrote an article about it for Twins magazine. I wrote about our adoption for Roots & Wings. I read every book I could find about twins, about parenting very young children, etc.

I’m getting things all muddled and in the wrong order. The summer the girls turned two, I remember I was so behind in my studies that I had to “read” — I am using the term loosely — one book on 19th century American literature each day. I would take the girls into the back yard where we had a little inflatable wading pool with a whale spout and they would leap in and out of the pool, squealing, while I frantically  skimmed pages and jotted notes.

skimmed pages and jotted notes.

I started my full-time, tenure-track job the year Annie and Pearl began kindergarten. The following June, we adopted Emma. (At that point, friends did tell me I had lost my mind. They weren’t wrong.)

Maybe I need to write a “real” essay about all of this. Maybe I can stop scribbling for now.

It was a wild ride — I didn’t even get to the teenage years, did I? I’m sometimes upset that my daughters turned out so “different” from me, their values, their passions — not a poem in sight! I have been known to threaten moving to a stone cottage on the west coast of Ireland and throwing away my cell phone. But they keep coming around, they keep talking to me, and I keep being (unreasonably) happy when they do. I spoke with my pastor recently about some upsetting thing or other, and he recommended that I read You and Your Adult Child. He was reading it, he disclosed, “And it’s helping.” Finding other parents (writers, especially) has turned out to be crucial.

This morning I decided to reread Rose Cook’s poems (I’m lending the book to a friend). And I found this poem:

On Bringing Up Girls

Aren’t you going to clip her wings?

they said, That’s usual for a girl her age, isn’t it?

We said we didn’t want to clip her wings

and they watched our little daughter grow

bright and strong, then they saidAren’t you going to tie her feet? That’s

advisable for young girl, isn’t it?

We said we didn’t want to tie her feet,

so they saw a young woman growing

clear and brave. Before they could say anything else

we said, Now it is time to teach her to fly.

They fell back.They are teaching her to fly, they repeated,

teaching her to fly.

How wonderful, murmured their daughters,

and how interesting.— Rose Cook, from Notes from a Bright Field (Cultured Llama Publishing, 2013)

I once read this little meme — the girls were probably 12, 12, and 6 — that went, “If humans had wings, we’d consider flying to be exercise and never do it.” I read this aloud, and my daughter Pearl turned to me with wide eyes and said, “If I had wings, I would fly!”

And — in their way — I’m sure they do.

I have kept a journal since I was a teenager. There were earlier abortive attempts, for instance, a Christmas-gift diary with a key when I was eleven or so. Then, in 10th grade, Miss Caughey (pronounced Coy) assigned her students to keep a journal. We may have been reading Anne Frank.

I have kept a journal since I was a teenager. There were earlier abortive attempts, for instance, a Christmas-gift diary with a key when I was eleven or so. Then, in 10th grade, Miss Caughey (pronounced Coy) assigned her students to keep a journal. We may have been reading Anne Frank. filled 35 of them. Just this morning, I began the 36th, the last one I have on hand. I checked the online catalog and though they used to cost a reasonable $18.95, they are now priced $31.90. All paper supplies have gone up lately, my friend reminded me. These are handsome books with lined pages, 400 pages, plus index pages.The quality of their paper allows for double-sided writing (cheaper notebooks, not so much), so they are probably still worth it.

filled 35 of them. Just this morning, I began the 36th, the last one I have on hand. I checked the online catalog and though they used to cost a reasonable $18.95, they are now priced $31.90. All paper supplies have gone up lately, my friend reminded me. These are handsome books with lined pages, 400 pages, plus index pages.The quality of their paper allows for double-sided writing (cheaper notebooks, not so much), so they are probably still worth it.

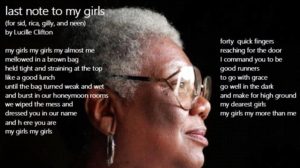

At the reception after the reading, another young poet started telling Clifton all about herself. I knew it was nerves, but it was still a little stunning to see her binge-talk through the entire conversation. When she walked away, Clifton said, laughing, “Does she ever listen? How does she ever learn anything?”

At the reception after the reading, another young poet started telling Clifton all about herself. I knew it was nerves, but it was still a little stunning to see her binge-talk through the entire conversation. When she walked away, Clifton said, laughing, “Does she ever listen? How does she ever learn anything?”

If you have been my student or talked about writing with me, then you probably already know that Priscilla Long, author of The Writer’s Portable Mentor and other books, has been my friend for 30 years.

If you have been my student or talked about writing with me, then you probably already know that Priscilla Long, author of The Writer’s Portable Mentor and other books, has been my friend for 30 years.