Naomi Shihab Nye’s Transfer

Thanks to Dave Bonta at the blog Via Negativa, and his twitter feed, I’ve been spending a little time over the last couple of days with other poetry bloggers. (It was a lovely surprise to find a bunch of retweets leading me to bethanyareid.com. Someone IS reading me!)

This infusion of enthusiasm came just in time. Maybe because I had just gotten my own poetry manuscript off to an editor, maybe because I spent the weekend awash in poetry, maybe because someone at Goodreads asked if the project wasn’t going to give me “poetry indigestion” — I was questioning my purpose. But, then, the tweet, the blogs, and the books themselves renewed me.

No indigestion here. It was my great pleasure to spend the day with Naomi Shihab Nye, one of my poetry heroes. I learned yesterday that she will be speaking in at WWU in Bellingham on April 28 and I immediately recruited some compatriots in the land of poetry and made our reservations.

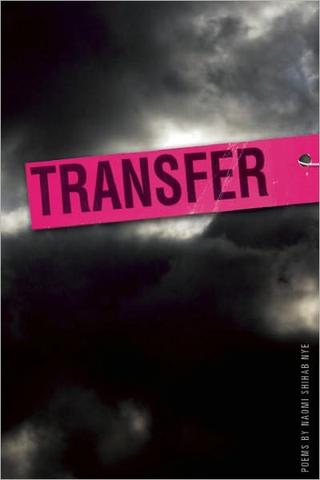

I also — since I was at Village Books when I saw the poster — picked up a copy of her 2011 book, Transfer (another poetry book, Bethany? really?). Worth it.

Transfer is a a tribute to Shihab Nye’s father, Aziz Shihab, who was a journalist and died of kidney failure and heart complications in 2007. The book includes some of his own words. I loved every poem. I took a picture of one poem, “Last Wishes,” about a 95 year old woman, and sent it to my friend Carolynne who just threw a birthday party for a 90 year old neighbor. I read lines aloud to my daughter. I wrote down these lines in my poetry journal: “There’s a way not to be broken / that takes brokenness to find it” (“Cinco de Mayo”). She manages to write out of and about her experience as a Palestinian American, and at the same time to capture what crosses and transcends cultural boundaries and speaks directly to my human heart. Her father was always looking for a home in the world, she tells us. At the same time, he — and his daughter — seemed to have found that home, in poetry, in writing, in family and friends, in acts of radical kindness to strangers.

Her poem “Kindness” is in my 2015 post, which you can find here. And here is a poem whose title came from her father’s notebooks:

I remember once being told that you can’t write poems about the moon — it’s been done too often. But at Litfuse, when

I remember once being told that you can’t write poems about the moon — it’s been done too often. But at Litfuse, when