To register for the book launch of Our Deepest Calling, Saturday, April 17, at 4 p.m. , follow this link: https://www.villagebooks.com/event/litlive-chuckanut-sandstone-0401721. (And if you are wondering where the images are in this post, for some reason today I’m not able to upload new ones.)

Our deepest calling is to grow into our own authentic self-hood, whether or not it conforms to some image of who we ought to be. As we do so, we will not only find the joy that every human being seeks—we will also find our path of authentic service in the world.”

—Parker Palmer

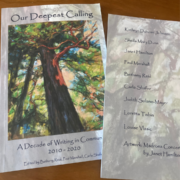

Thanks to Village Books in Fairhaven—and Zoom—tomorrow at 4 p.m. my writing group will be celebrating the publication of a collection of poetry and prose written during our first ten years together. Our Deepest Calling is also available for purchase through Village Books ($16 and $1 shipping).

I’m taking a day off from writing something new for the blog, and reproducing here my introduction to Our Deepest Calling (fleshing it out a bit for people not familiar with the context given in my co-editor’s intro), followed by a sampling of poems. The book also includes short essays and an excerpt from a novel in progress.

“I learned how to write in the interstices of daily life.”

—Maxine Kumin

In 2010, when my dear friend Paul Marshall asked me if I would lead a Teaching Lab under the auspices of the Teaching and Learning Cooperative at Everett Community College, my first response was “oh, no.” That evening after supper and homework, one of my teenaged daughters had a meltdown over a boyfriend; another was fighting with her best friend; the ten-year-old didn’t want to go to bed; and my sister called to tell me that I really really needed to help out more with our aging parents. The next morning, instead of retreating into the pages of my journal, I graded a set of student papers. Then I thought, What if we called it a Teaching Lab, but wrote instead?

Our first meeting attracted a couple dozen people from across campus—staff, faculty, and even administrators. It was wild. In my recollection, we were before too long half that number, and soon we were only eight or so souls. No matter, we were committed. Our first year we worked through Susan M. Tiberghien’s One Year to a Writing Life: Twelve Lessons to Deepen Every Writer’s Art and Craft. By the second year, we all had our own projects underway and settled into a routine of just writing. Some of our colleagues were skeptical, to put it mildly: What are you doing in there, and what does it have to do with teaching?

To my mind, the Writing Lab had everything to do with…everything. Our sessions were only ninety minutes once a week—but that bit of time and each other’s encouragement were all we needed to keep the flame of our writing, questing and questioning lives burning.

Ten years ago, I was immersed in the daily catastrophe of full-time teaching and raising a family. Now that I’m retired from the college and my daughters are grown and out of the house, now that my parents have passed on, I have more time, or so I tell myself. Other group members have gone through similar transitions, all of which are reflected in our writings, no matter if we write of fortune cookies, jump ropes, or imaginary trysts with former U. S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins.

Then along comes 2020 with new challenges, and its catastrophes on a global scale. Our writing group is now even more important to me, as we have over the years become a group of friends who listen deeply to one another and among whom we know we will be heard.

“Oh friends, where can one find a partner for the long dance over the fields?”

—William Stafford, from A Walk in the Country

I should add that, since moving ourselves off-campus to Rosehill Community Center near the Mukilteo Ferry Dock (and, this past year, to Zoom), we have morphed into an eclectic bunch of former EvCC people and community members. One of these is the award-winning artist Janet Hamilton, whose painting, “Madrona Concerto,” graces our cover.

Here is a poem from co-editor (and Zoom-master) Carla Shafer:

Ancestors

Because my family has lived on stolen tribal

lands in the northwest since I was born, I listen

to the bending of the trees, follow the paths

of salmon and walk days short in winter and

long in summer. This is not the place of my

ancestors. This is not Bohemia or Baden-Baden.

It is not the Nebraska plains or Kansas prairies.

I am not at the source of my great-grandparents’

imaginings, but their touch is in my hand, their

hopes carried in my heart, their steps are known

just as the salmon wiggles a fin,

and in the sway of a cedar bough.

My grandsons, living near, speak Japanese, the language

of their mother’s family, celebrate Children’s Day

and imagine beyond boundaries and borders. My

daughter’s child will speak Hindi and Urdu,

celebrate Eid al Fitr. Their paths of succession will move

through hazards in shadow and light. They will view

stars across generations who have danced

on the same side of the moon. Their ancestors

traced in their steps, in the twinkle of their eyes,

in the embrace of what comes next, beneath the flight

of peregrine falcons, above waters where Orcas swim.

—Carla Shafer

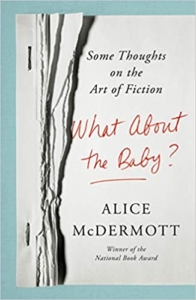

If you are still wondering what to buy the fiction-writer on your Christmas list, I am happy to recommend Alice McDermott’s What about the Baby?: Some Thoughts on the Art of Fiction (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

If you are still wondering what to buy the fiction-writer on your Christmas list, I am happy to recommend Alice McDermott’s What about the Baby?: Some Thoughts on the Art of Fiction (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

This past Sunday I attended my childhood church and there, too, the message was drawn from one of those leading-up-to Christmas passages in the book of Luke. I have to set the stage here a bit, if you’re to follow where I’m going (which is, my apologies, not quite clear even to me). The couple who now pastor the church are in their 80s. My parents would have loved them. This ministry is a definite calling for the Bakers, and it came quite late in life. So when “Sister Baker” (as we say) talked in her sermon about the angel Gabriel visiting Zechariah, to tell him his wife Elizabeth, “well stricken in years,” would bear a child, a precursor to Christ — well, she had a personal response.

This past Sunday I attended my childhood church and there, too, the message was drawn from one of those leading-up-to Christmas passages in the book of Luke. I have to set the stage here a bit, if you’re to follow where I’m going (which is, my apologies, not quite clear even to me). The couple who now pastor the church are in their 80s. My parents would have loved them. This ministry is a definite calling for the Bakers, and it came quite late in life. So when “Sister Baker” (as we say) talked in her sermon about the angel Gabriel visiting Zechariah, to tell him his wife Elizabeth, “well stricken in years,” would bear a child, a precursor to Christ — well, she had a personal response.

So, about a week ago I thought I would write a blogpost inspired by Steven Pressfield, about…pain. I copied Pressfield’s recent post and linked it (see bottom of page), and I added this passage from the painter Grant Wood:

It’s all very wise and was meant to encourage me to push through a rough patch. But it really just made me feel the complete opposite of encouraged. I wanted to go back to bed.

On a whim I googled “DELIGHT,” and it took me straight to J. B. Priestley’s book Delight, published in 1949. Not long ago my husband and I watched the 2018 film of Priestley’s play, An Inspector Calls, so this seemed like one of those synchronicities that we ought to pay attention to. I bought the book, downloaded it, and, well, was delighted.

In the preface, Priestley begins, “I have always been a grumbler.” He goes on to explain the benefits (the delights?) of a good grumble. But then we get 114 short chapters on what delights him: reading detective stories in bed, lighthouses, waking to the smell of bacon, the ironic principle, orchestras tuning up, making stew, departing guests. Some of it is a little dated (the stereoscope, wearing long trousers, and several chapters about the delights of smoking). But it’s also a window into Priestley’s time (1894-1984), bits of a lost world.

I’m rushing off to a task this morning (and finishing it will delight me), but here’s a post from another blog that does a better job than I have time for: https://www.stuckinabook.com/delight-jb-priestley/

And that’s your assignment for this week. Sure, I hope you sometimes push through, dig deep, suffer for your art, but meanwhile: what delights you? I’d love to hear about it.