Christmas Stories

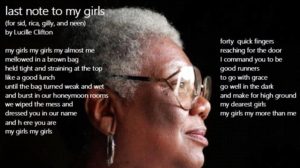

I was just over at Salt and saw that they have three poems by Lucille Clifton — a one-of-a-kind human being and poet I was privileged to hear in person a few times. Salt had a Christmas poem by Billy Collins last week (also worth a visit), and in this week’s offering, keeping faith with the season, Clifton’s poems, “mary’s dream,” “a song of mary,” and “john,” i.e. John the Baptizer.

This past Sunday I attended my childhood church and there, too, the message was drawn from one of those leading-up-to Christmas passages in the book of Luke. I have to set the stage here a bit, if you’re to follow where I’m going (which is, my apologies, not quite clear even to me). The couple who now pastor the church are in their 80s. My parents would have loved them. This ministry is a definite calling for the Bakers, and it came quite late in life. So when “Sister Baker” (as we say) talked in her sermon about the angel Gabriel visiting Zechariah, to tell him his wife Elizabeth, “well stricken in years,” would bear a child, a precursor to Christ — well, she had a personal response.

This past Sunday I attended my childhood church and there, too, the message was drawn from one of those leading-up-to Christmas passages in the book of Luke. I have to set the stage here a bit, if you’re to follow where I’m going (which is, my apologies, not quite clear even to me). The couple who now pastor the church are in their 80s. My parents would have loved them. This ministry is a definite calling for the Bakers, and it came quite late in life. So when “Sister Baker” (as we say) talked in her sermon about the angel Gabriel visiting Zechariah, to tell him his wife Elizabeth, “well stricken in years,” would bear a child, a precursor to Christ — well, she had a personal response.

Zechariah tried to tell Gabriel it just couldn’t happen. We’re too old, he said. So he had to be struck mute. As Sister Baker said, when God has a plan, if you can’t get on board, he may ask you to get out of the way. Then — this was her personal response — she added, “I sure hope Gabriel doesn’t show up and tell me I have to have a baby, at my age.” Everyone laughed.

I’m not quite sure where I’m going with this, except for the last two days I’ve been wondering how I can work this anecdote into a poem. It’s easier to imagine a challenge for the fiction writers in my group:

Write a scene in which a character attends a church service and hears a message that makes him or her uncomfortable.

I hadn’t been too sure about this trip, but the church service itself didn’t make me at all uncomfortable. My brother and sister and their spouses were there (my brother said at lunch that he was surprised the church didn’t fall down); also one my of aunts (age 86), and about a dozen of my cousins from all over Southwest Washington. Lots of music. I did a complete flashback to my childhood and wept. Much has changed (the drums and guitars up front), and I knew only two of the people in their small congregation. But there was a time for personal testimony, and an altar call at the end — both could have been scripted from a service when I was seven.

I’ve been rereading Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, and this morning I underlined this line:

“our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost” (p. 6).

That’s kind of the space my thoughts are hovering over.

Here’s one of the poems from Salt:

mary’s dream

winged women was saying

“full of grace” and like.

was light beyond sun and words

of a name and a blessing.

winged women to only i.

i joined them, whispering

yes.–Lucille Clifton

Mostly, I’ve been wondering what’s calling me right now — what’s completely unexpected and calling me — and how to say “yes” to it.

At the reception after the reading, another young poet started telling Clifton all about herself. I knew it was nerves, but it was still a little stunning to see her binge-talk through the entire conversation. When she walked away, Clifton said, laughing, “Does she ever listen? How does she ever learn anything?”

At the reception after the reading, another young poet started telling Clifton all about herself. I knew it was nerves, but it was still a little stunning to see her binge-talk through the entire conversation. When she walked away, Clifton said, laughing, “Does she ever listen? How does she ever learn anything?”