Your Poetry Assignment for the Week

Every Wednesday afternoon I meet—either on Zoom or in person, if our outdoor cafe is a safe bet—with several other writers. We have two dedicated novelists, but the rest of us write mostly poetry. All of us, I should add, write poetry sometimes.

We’ve been meeting for 11 years. I think of myself as the facilitator of this group; they think of me as their fearless leader. Every Tuesday I email them a reminder and a poem (or, I send them a poem if I’m not too lazy and don’t forget) that they are welcome to think of as a prompt. I usually add a few sentences commenting on the poem. There are no rules in our group, but usually one or two writers end up bouncing off some idea this process has introduced. A while back we played around with a triolet by Barbara Crooker and I was tickled to see people still wrestling with the form last week.

Sometimes I send a poem, or a poet, that I’ve blogged about. Lately I’ve been telling myself that I really ought to  blog once a week, and what if I married these two tasks together? This is my attempt to make it so.

blog once a week, and what if I married these two tasks together? This is my attempt to make it so.

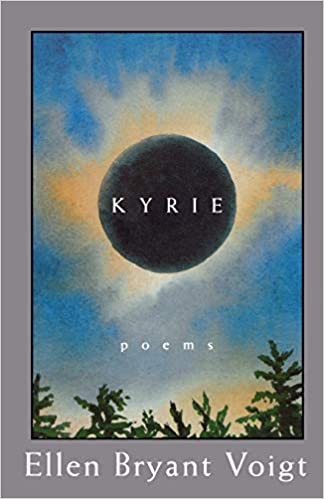

I’ve been reading Ellen Bryant Voigt’s 1995 book Kyrie, a series of poems set in 1918—during the (yep) flu epidemic. One poem begins “How we survived…” that is a perfect prompt, but it has an image in it that so freaked me out I don’t want to share it. I cast around, reading poem after poem: “You wiped a fever-brow, you burned the cloth. / You scrubbed a sickroom floor, you burned the mop. / What wouldn’t burn you boiled like applesauce / out beside the shed in the copper pot.”

And there’s this poem, the first in the collection, which seems to predict the future of that survival:

Prologue

After the first year, weeds and scrub;

after five, juniper and birch,

alders filling in among the briars;

ten more years, maples rise and thicken;

forty years, the birches crowded out,

a new world swarms on the floor of the hardwood forest.

And who can tell us where there was an orchard,

where a swing, where the smokehouse stood?—Ellen Bryant Voigt

My interest in Voigt’s book is personal, something to do with a novella I’d like to write; something to do with working on a manuscript of poems about a farm.

I am also compelled to tell you that I’m nearly all the way through a riveting memoir, House Lessons: Renovating a Life, by local author Erica Bauermeister. When her children were young, Bauermeister and her husband had the crazy idea to rescue a derelict house in Port Townsend and—well, you just have to read it to believe it.

My husband was, once upon a time, a building contractor, so, reading, I think: “Why didn’t we ever do something like this?” And then, reading on, I’m amazed at the work—when did she ever get any writing done? When 9 / 11 interrupts their progress, I found myself wanting to pick up the Voigt poems again. There’s a resonance between the two narratives that I wish I were more equal to describing. It has something to do with putting notes inside walls for future owners to find.

We create stories with beginnings, middles, and ends, and then cast them out into the world, talismans against the reality that life does not always tie up neatly, that it can come at you sideways, take away your breath, your life, your sustaining belief that everything will end up okay. We write our stories on paper, like wishes on New Year’s, and send them out into the world.

—Erica Bauermeister

In a summer when I’ve been feverishly reading doomsday accounts of what will happen to our planet because of climate change, it’s nice to imagine rescuing one house; it’s comforting to imagine how a family comes out the other end of a devastating world war and a pandemic; it’s even weirdly satisfying to imagine smashing down a wall with a sledgehammer.

In a summer when I’ve been feverishly reading doomsday accounts of what will happen to our planet because of climate change, it’s nice to imagine rescuing one house; it’s comforting to imagine how a family comes out the other end of a devastating world war and a pandemic; it’s even weirdly satisfying to imagine smashing down a wall with a sledgehammer.

So that’s your prompt this week. Cast yourself into the future and, looking back from that vantage, tell us, How did you survive?