Forrest Gander, Twice Alive

TWICE ALIVE: AN ECOLOGY OF INTIMACIES, Forrest Gander. New Directions, 80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011, 2021, 84 pages, $16.95 paper.

I knew Forrest Gander only as the partner of the poet C. D. Wright (1949-2016), until I attended a 2018 presentation of Pablo  Neruda’s Then Come Back: The Lost Neruda, translated by Gander.

Neruda’s Then Come Back: The Lost Neruda, translated by Gander.

The author of numerous books, poetry and prose, Gander is also a celebrated translator and collaborator. I eagerly read his previous book of poems, Be With, and now this one. And while I find him quirky and hard to capture, I’m grateful for these books. He cares deeply about language, languages, and about people as well as plants and planet.

At the New Directions page for Twice Alive, I found these words, which explain a lot in a little space:

“While conducting fieldwork with a celebrated mycologist, Gander links human intimacy with the transformative collaborations between species that compose lichens. Throughout Twice Alive, Gander addresses personal and ecological trauma—several poems focus on the devastation wrought by wildfires in California, where he lives—but his tone is overwhelmingly celebratory. Twice Alive is a book charged with exultation and tenderness.”

The loss of his partner is pretty clearly part of the loss addressed in this book. I want to say “embraced” in this book. It’s a weird book, where nothing seems off-limits. Consider the opening stanza of the title poem, “Twice Alive”:

Mycobiont just beginning to en-

wrap photobiont, each to become

something else, its only life and a

contested mutuality, twice alive,

algal cells swaddled in clusters

As in other books I’ve read and blogged about this month, the layout of many of the poems here is challenging. I was intrigued by the layout of the Aubades (meaning a morning love song, or a poem about lovers parting at dawn):

Aubade III

We were servicing the pools of the wealthy • we were opening the

passenger door for the dog • the dog who waits in the truck • dog

staring at the restaurant entrance • so when we come out again

with a napkin • wrapped around a chunk of burrito • whimpers

with excitement • and we don’t • feel entirely alone • through it’s

true • Yo, la peor de todas • at Arion the printers • were dampen-

ing linen • so the type would cast a shadow • before they tossed

slugs of type • back into the hellbox • in the evening • we tried

to cure a phantom • limb with a mirror • but what is missing • is

inside us. A few were • throwing gang signs and smoking Reggie

• before we boarded at pre-dawn • to sit forever on the runway •

sucking up the spent fuel • of the plane before us • the overhead

ducts spewing noxious air • reflected in the dark window • our

own eyes looking back • looking blank • while neutrinos sleet

through us—Forrest Gander

You can learn more about this poet and this book at Poetry Foundation. I’m also happy to recommend Gander’s website, where I found interesting offerings under both the media and news tabs.

And see this New Yorker piece on Gander’s book dedicated to C. D. Wright, Be With, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2019.

One epigraph from the opening of Twice Alive:

a garden without lichens / is a garden without hope –Drew Milne

There is—as you can see from the excerpts I’ve included here—a lot of unease, if not outright alarm in these poems. But also hope.

thumping, amazing book about family, exile, separation, death, and identity. Salvadoran-American poet Regalado knows whereof she speaks. In the words of Reginald Dwayne Betts, who chose Reliquenda for the National Poetry Series,

thumping, amazing book about family, exile, separation, death, and identity. Salvadoran-American poet Regalado knows whereof she speaks. In the words of Reginald Dwayne Betts, who chose Reliquenda for the National Poetry Series,

aspirational Bethany Reid poems. But today’s book spun me, and made me want to tear everything down and start over.

aspirational Bethany Reid poems. But today’s book spun me, and made me want to tear everything down and start over.

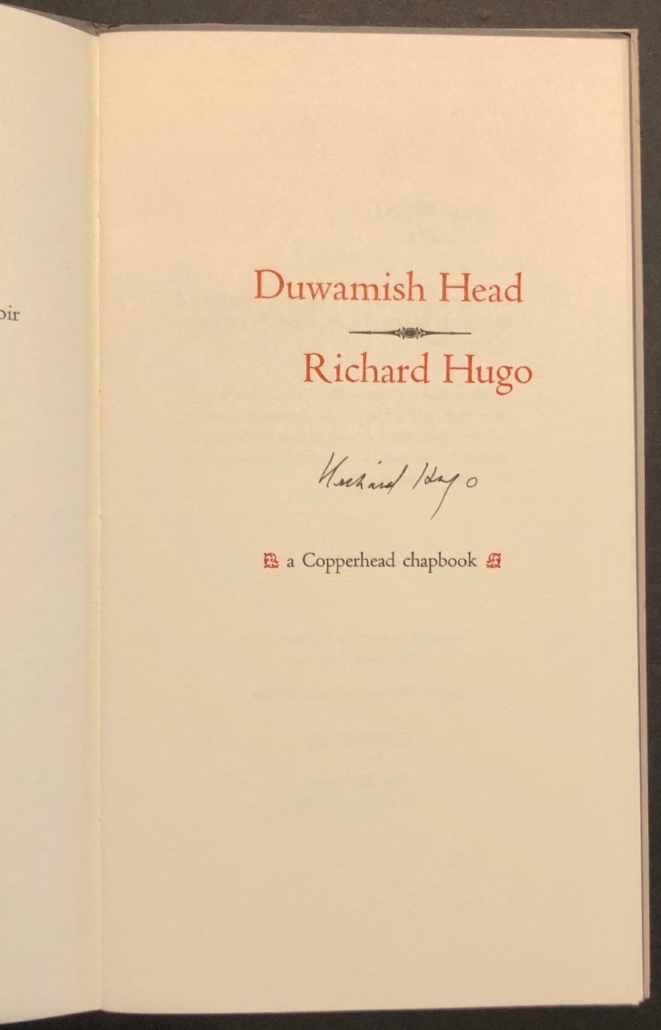

Richard Hugo, recently passed along to me by a friend who was letting go of some books. Copperhead no longer exists, and I couldn’t find any mention of it when I searched, but I suspect it was a precursor of Copper Canyon, as this chapbook was produced by Sam Hamill and Tree Swenson.

Richard Hugo, recently passed along to me by a friend who was letting go of some books. Copperhead no longer exists, and I couldn’t find any mention of it when I searched, but I suspect it was a precursor of Copper Canyon, as this chapbook was produced by Sam Hamill and Tree Swenson.