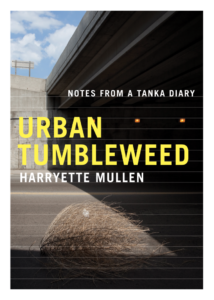

Harryette Mullen, Urban Tumbleweed

URBAN TUMBLEWEED: NOTES FROM A TANKA DIARY, Harryette Mullen. Graywolf Press, 250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600, Minneapolis, MN 55401, 2013, 127 pages, $15 paper, www.graywolfpress.org.

In 2020 I mentioned to a friend that I had been writing poems about my daily walks, and she dug around in her bookbag, pulled out Urban Tumbleweed, and gave it to me on the spot. At home, I read a page or two, here and there, and then put it away “for later.” I am really, really glad that I took it down this morning. Although individual tankas can delight—

The determination of a turtle

clambering out of a pond, up the slippery

side of a rock to rest in the sun. (p. 18)

—I discovered further pleasures by reading it all the way through at one go.

At the entrance to the botanical garden,

a sign hung on the gate forewarns: “Slow down.

Watch for turtles on the roads and paths.” (p. 47)

Mullen explains her project in the foreword:

My tanka diary began with a desire to strengthen a sensible habit by linking it to a pleasurable activity. I wanted to incorporate into my life a daily practice of walking and writing poetry. As committed as I am to writing, I needed a break in my routine, so I determined to alter my sedentary, unconsciously cramped posture as a writer habitually working indoors despite living here in “sunny California.” (p. vii)

A professor of creative writing and African American literature at UCLA and the author of seven more conventional poetry books (notably, Sleeping with the Dictionary, which was a finalist for the National Book Award), Mullen adapts the traditional form of the Japanese verse of thirty-one syllables (originally printed as a single line of text, in English generally broken into five lines of 5-7-5-7-7) to suit herself. Each of her tankas is close to 31 syllables, but rendered in three lines. The main point was to walk, pen and notebook in her pocket, each day writing a single observation:

Another goal was to address the question, “What is natural about being human?” While Mullen’s observations are often about the natural world, they don’t stray far from newspaper stories, bus riders, and trash.

Along the roadside, someone has spilled

pink Styrofoam peanuts. They add color

to the grassy green, but I still prefer flowers. (p. 13)Ha-ha-haw-haw, the dark bird’s rowdy laughter

as it flew over the heads of earthbound

pedestrians who didn’t get the joke. (p. 115)

In The Art of Voice: Poetic Principles and Practice, Tony Hoagland asks a question I’ve been pondering this month:

In The Art of Voice: Poetic Principles and Practice, Tony Hoagland asks a question I’ve been pondering this month:

What do we want from a contemporary poetic voice? One good answer to that question is that we want to feel that we are encountering a speaker “in person,” a speaker who presents a convincingly complex version of the world and of human nature. When we commence reading a poem, we are starting a relationship, and we want that relationship to be with an interesting, resourceful companion. (p. 5)

I find that this is also true with an entire book of poetry. And even when I start out with some reluctance, I find that if I keep going I inevitably begin hearing the poet’s voice, maybe trusting it, definitely glimpsing the world through new eyes. At least, that’s how I felt this morning, reading Harryette Mullen’s 366 tankas. I have a feeling that her journey, in writing the poems, was much the same.

Although I don’t expect that I will soon burst into a book-length experiment with the tanka, I have decided to start carrying a notebook on my walks.

To read more about Harryette Mullen, follow this link.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!