Linda McCarriston, Eva-Mary

EVA-MARY, Linda McCarriston. Tri-Quarterly Books, Northwestern University, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208, 1991, 78 pages $10.95 paper.

A friend gave this book to me in 1993, the year my twins were born. I don’t know when I read it, though I know I  eventually did. Since then—for most of the last thirty years—it has been shelved above my writing chair with a lot of other poetry books.

eventually did. Since then—for most of the last thirty years—it has been shelved above my writing chair with a lot of other poetry books.

I meant to write about another poet today, and their 2023 book of poems, but for some reason this morning I took down Eva-Mary and opened it to the first poem, “The Apple Tree,” dedicated to the poet’s mother. “Oh, yes,” I thought. “I remember this book.”

I was misremembering it.

Yes to blossoms, yes to family kitchens, yes to horses, yes to Irish ballads. But also yes to women raped with rifle barrels, to incest, to judges ordering women home to abusive husbands, priests ordering bruised daughters, “Mind your father.” The time-line stretches into adulthood, into divorce and custody battles. Even so, Eva-Mary is beautifully wrought, the winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry, a finalist for the National Book Award, in its 3rd printing by the time it came to me. I read every page (as if I’d opened a dystopian novella, I couldn’t pry my eyes away), and even so I can’t seem to offer this review without a trigger warning.

One reads this book, from the second poem (“To Judge Faolain, Dead Long Enough: A Summons”) onward knowing exactly what the subject matter is, so I’m not giving away the content. And, on the chance that one of my readers needs permission to write her or his own devastating truth, I am happy to recommend this book. McCarriston does it brilliantly. (You could take nothing away but the metaphors and be redeemed.)

I know that I read this book, by the way, because I can see the ways in which it influenced my own writing. Here is perhaps my favorite McCarriston poem in this collection:

A Thousand Genuflections

Winter mornings when I call her,

out of falling snow she trots

into view, her tail and mane

made flame by movement, carrying,

as line and motion, back into air

her shape and substance—like fire

into heat into light, turns

the candle takes, burning.

And her head—her senses,

every one a scout sent out

ahead of her, behind, beside:

Her eye upon me, over the distance,

her ear, its million listeners,

delicate and vast her nose, her mouth,

her voice upon me, closing the distance.

I could just put the buckets down

and go, but I kneel to hold them

as she eats, as she drinks, to be

this close. For something of myself

lives here, stripped of the knowing

that is not knowing, a single thing

from the least webbed tissues

of the heart straight out to the tips

of the guard hairs that shimmer off

beyond my sight into air, the grasses,

grain, the water, light.

I’ve come like this each day

for years across the hard winters,

seeing a figure for the thing itself,

divine—appetite and breath,

flesh and attention. This morning

her presence asks of me: And might

you be your body? Might we be

not the figure, but the thing itself?—Linda McCarriston

Among these poems (not to mention among horses) there is also great power to bless and console.

I’ve now learned that McCarriston wrote on, winning many awards. She is professor emeritus at the Low-Residency Creative Writing Program, University of Alaska, Anchorage, and you can learn more about her at Poetry Foundation and on her page at UAA.

At Poetry Foundation, I found another horse poem that I am compelled to share: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?contentId=35181

The poems in A Nail the Evening Hangs On are not those poems.

The poems in A Nail the Evening Hangs On are not those poems.

If I had to characterize her in one word, it would be “storyteller.” Yes, she taught us (a lot) about poetry and the making of poems, but part of the glamor of her classes, for me, was when she would lean back in her chair, half-close her eyes, and begin telling a story. She put all of us in a trance.

If I had to characterize her in one word, it would be “storyteller.” Yes, she taught us (a lot) about poetry and the making of poems, but part of the glamor of her classes, for me, was when she would lean back in her chair, half-close her eyes, and begin telling a story. She put all of us in a trance.

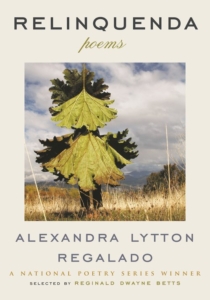

thumping, amazing book about family, exile, separation, death, and identity. Salvadoran-American poet Regalado knows whereof she speaks. In the words of Reginald Dwayne Betts, who chose Reliquenda for the National Poetry Series,

thumping, amazing book about family, exile, separation, death, and identity. Salvadoran-American poet Regalado knows whereof she speaks. In the words of Reginald Dwayne Betts, who chose Reliquenda for the National Poetry Series,