Ed Harkness

THE LAW OF THE UNFORESEEN, Poems by Edward Harkness. Pleasure Boat Studio, 3710 SW Barton St., Seattle, WA 98126, 2018, 116 pages, $14, paper, pleasureboatstudio.com.

THE LAW OF THE UNFORESEEN, Poems by Edward Harkness. Pleasure Boat Studio, 3710 SW Barton St., Seattle, WA 98126, 2018, 116 pages, $14, paper, pleasureboatstudio.com.

In the cover notes, Anne Pitkin describes Ed Harkness’s poems as riding “a current of melancholy, a certainty of loss which deepens the vitality.” A northwest native, Harkness writes about his travels at home and abroad and reaches back through time to share the paths his ancestors took before him. And, in this poem, Walt Whitman joins the chorus.

Today’s poem suggests a great poetry prompt. What would happen if you invited a poet from the past (Dickinson, Rilke, Yeats?) to join your morning walk? What will they notice that you might otherwise miss? What snippets from their poems might you weave in? What will the two of you talk about as you meander?

Whitman Reading by Moonlight

Walt Whitman pads around on the lawn

in bathrobe and slippers. Moonlight

silvers the lilac tree by the dooryard,

the flowers long gone from lavender to rust.

He opens his notebook to read a recent draft,

the title appearing as–he can’t make it out–

“Growing Broken Berry,” it looks like.

Back in bed he sees himself forlorn,

alone on the stern, riding the Brooklyn Ferry,

his shirt collar turned up, his fingers

clutching the brim of his straw hat.

He opens his notebook and reads aloud

by moonlight a draft, its working title:

“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” In bed,

staring at the blank screen of the ceiling,

he watches himself tear out one page

from the notebook, then another.

When he releases them, they rise like gulls

aloft on the back draft, awhirl in a billow

of coal smoke and steam. Pages flutter

ungainly, as if wounded, alighting

on the wake’s white fire where they swim,

swirl, flatten and disappear

into the black waters of the Hudson.

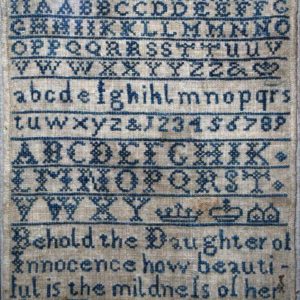

ABCS OF WOMEN’S WORK,

ABCS OF WOMEN’S WORK,

THE OLD REFUSALS, Carmen Germain, Moon Path Press, P.O. Box 445, Tillamook, OR 97141, 2019, 64 pages, $16 paper, http://MoonPathPress.com

THE OLD REFUSALS, Carmen Germain, Moon Path Press, P.O. Box 445, Tillamook, OR 97141, 2019, 64 pages, $16 paper, http://MoonPathPress.com

THE LURE OF IMPERMANENCE, Carey Taylor, Cirque Press, 3978 Defiance Street, Anchorage, AK 99504, 2018, 73 pages, $15 paper,

THE LURE OF IMPERMANENCE, Carey Taylor, Cirque Press, 3978 Defiance Street, Anchorage, AK 99504, 2018, 73 pages, $15 paper,