Abbey of the Arts

I’m blissed-out and and blessed. My daughters and their SO’s are coming to dinner. Hubby is in the kitchen (cooking up a storm). I woke up very, very early and put in two hours on my novel, then I had a long walk early this morning in the crisp cold air under blue skies. (Now, to bake pies!)

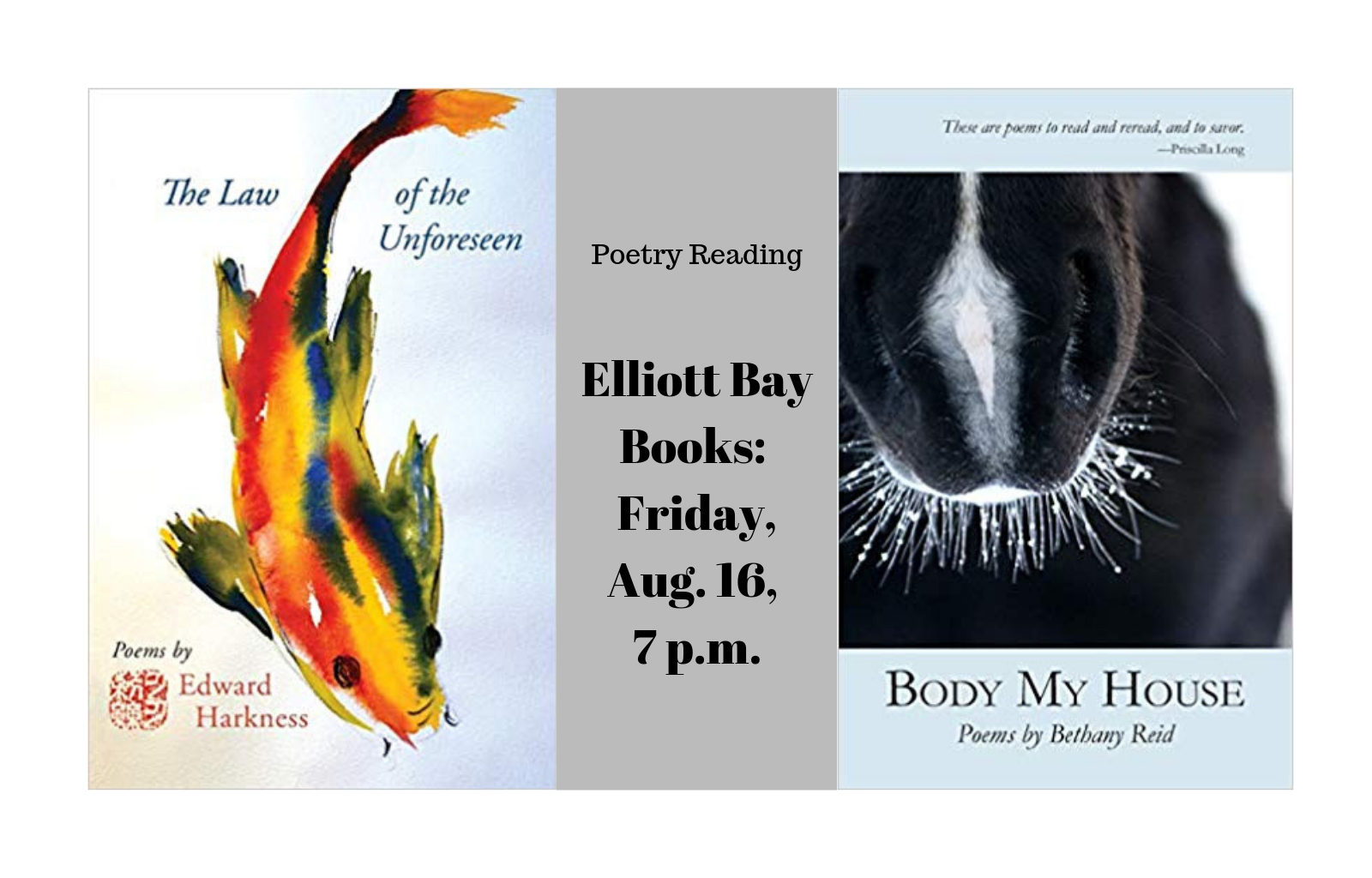

And — on the heels of two wildly successful readings last weekend, I discovered that my feature at Abbey of the Arts had gone “live” — so nothing but thanks, thanks and more thanks in the writing department. (I hope you’ll explore the entire Abbey site — it features the work and wisdom of poet and teacher Christine Valters Paintner and I’m confident you’ll agree that it’s a treasure.)

Then, taking a moment this morning to catch up on email — I found this delightful poem at a blog I follow, The Poetry Department…aka The Boynton Blog.

If you have been my student or talked about writing with me, then you probably already know that Priscilla Long, author of The Writer’s Portable Mentor and other books, has been my friend for 30 years.

If you have been my student or talked about writing with me, then you probably already know that Priscilla Long, author of The Writer’s Portable Mentor and other books, has been my friend for 30 years.